Does it seem that documentaries like Life in Color with David Attenborough sometime become repetitive? After all, we just saw the strawberry dart frog in Tiny World with Paul Rudd. What more can we learn? Apparently, quite a lot, but with the use of ultraviolet cameras and polarized lenses. Life in Color presents three episodes, Seeing in Color, Hiding in Color, and Chasing Color. The first two, though visually amazing, are pretty standard stuff, although they give a hint of what’s to come. It is the last episode that is most informative as you watch the scientists and cameramen film and explain their work. Now, we better understand why color conceals, confuses, and warns.

Humans have three color receptors. The peacock mantis shrimp has twelve and can detect polarized and unpolarized light. Many birds, insects, lizards, and fish can see in the ultraviolet range. Through the use of specialized cameras, Attenborough allows us to see the world as they see it, or sometimes can’t see it. Why is it that the zebra is quite visible to humans but survives in a hostile world of lions, hyenas, and cheetahs? Movement of the black and white stripes, visual blurring, confuses predators and insects that attack others in the area. We see the tiger as orange, but the chantal deer, with only two color receptors, sees orange as a muted shade of green. This allows the tiger to get close for the attack, at least until the three-receptored langur monkey sounds the alarm. I give Life in Color 3.5 Gavels and receives an 8.7/10 IMDb score.

Plot

Birds have vision far superior to mammals, insects almost as good as birds. The toucan of Costa Rico uses its vision to determine which fruit is ripe. The female peacock in India uses hers to select the male with the most spots on the six-foot long tail feathers. Vibrant color in the animal world indicates a stronger mate, better for evolutionary purposes. Yet, those are colors we humans can see. The fiddler crabs use polarized light to see birds far away. Bees use ultraviolet light to see landing strips on flowers that will guide them to nectar. Watch as the grouse in Scotland changes color in winter to hide. Be even more amazed as the pintailed wydah deposits its egg in a waxbill nest. Because the gape is so similar, the waxbill raises the whydah chick as its own to the neglect of its offspring.

Actors

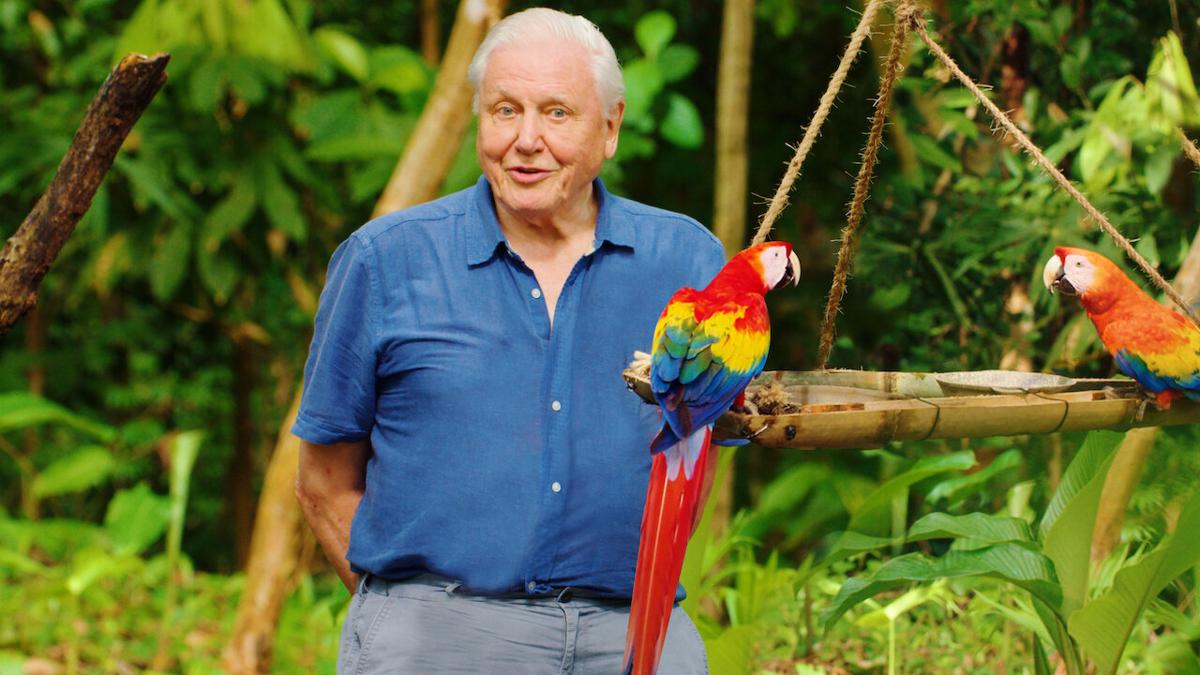

Is David Attenborough the Jacques Cousteau of the natural world? Would youngsters know the genesis of the song Calypso by John Denver? Then again, would youngsters know John Denver? Soon 95, Attenborough has been observing nature over a span of eight decades. Known as a national treasure, he has at least 32 honorary degrees from various universities.

Final Thoughts

The ultraviolet patch of the blue moon butterfly is a blessing and a curse. It attracts a mate but also attracts the birds. The red poison dart frog in Panama signals its poisonous nature to its predators. So, why shouldn’t others use the same color, even if not poisonous. The secret is that they do. Perhaps the most notable part of Life in Color is that scientists are just beginning to learn how nature uses color. There is much more than meets the human eye.

“Life In Color With David Attenborough is informative and visually stunning, of course, but the technology behind some of its more interesting scenes is what makes us want to keep watching.” Decider

“At first glance, the trailer appears as though it’s advertising your run-of-the-mill nature docuseries showcasing the ways in which animals use color to survive in the wild. About 30 seconds in, however, the trailer surprises viewers with an unexpected twist.” Collider.com

Even if you don’t watch the series, or just the third episode, I suggest you take two minutes and watch the trailer. It might change your perspective.